In the comics industry, special issues that promise one hero ?versus? another are usually long on gimmick and short on action. Keeping with that tradition my blog post promises an epic confrontation when in reality I?m not really engaging Graeber?s thought provoking essay ?Super Position? in a substantial way. I?m going to use the author?s Freudian critique of the summer blockbuster The Dark Knight Rises as catalyst to reflect on the anthropological study of popular culture.

As an aside I will say this about Graeber?s essay: he uses Roman numerals to demarcate thematic chunks of the essay, which allows him to write without transitions. Whenever I see this technique it always makes me think of Walter Benjamin, that patron saint of the Marxist critique of pop culture. To invoke Benjamin in an essay on Batman is like saying, ?I?m very serious about playing around here.? Or, at least that?s what I?m thinking when I write essays with Roman numerals.

I.

Graeber?s subject is Christopher Nolan?s series of Batman movies, which are themselves based on Frank Miller?s legendary characterization of the hero in ?The Dark Knight Returns? (1986), widely considered one of the greatest comic book stories of all time (and rightfully so). Miller?s book closed the door on the Silver Age version of the character and redefined the Gotham City universe as gritty and violent. Among the movie going public Miller is also known as the original author of Sin City and 300, while to the comics crowd he?s associated with legendary runs at Daredevil and Wolverine.

Miller himself is a reactionary ass and his slander of the Occupy movement as composed of ?louts, thieves, and rapists? was only the latest salvo in a stream of proto-fascist dribble. So when Graeber pins down the The Dark Knight Rises as ?anti-Occupy propaganda? he is pretty much on the money. A more patient man than I could probably connect the dots between the Reagan-era conservatism of ?Returns? with Rises. Neoliberalism and the apocalypse, maybe. Revenge, definitely.

What are superhero movies all about? And why are they so popular right now? These are the questions that prompted me to think about how anthropology could actually forward such a project. How ought we compose a research agenda focused on mass media and popular culture? Personally, I find myself consistently disappointed in most everything academics have written about pop culture. I?d like to think that anthropology could do better. What Graeber is doing here is using history and critical theory to write a polemic in order to make a political point. That?s fine, but it?s only one way that anthropology might go about designing research about comic book super heroes.

What could potentially make an anthropology of pop culture difficult is method. How, exactly, do you use ethnography to study it? There are a few entry points that could be alternatives to/ supplements for a theory-based cultural critique and they revolve around production and consumption.

Some ideas?

Production. Objective: study the ?backstage? process from creative talents to publishing and distribution. To be sure there is a difference in scale between the indies and the major labels but it all starts with a creative person or team having an idea. Role-model: ?Latinos, Inc.? by Davila ? the author conducts an ethnography of New York advertizing agencies focusing on how they imagine, study, interact with, and represent Hispanic markets through highly orchestrated advertising campaigns.

Consumption. Objective: learn what pop culture means to the people who love it. We call the cultural practice of consuming a comic book ?reading? and it is basically a private experience. You sit still, hold the book in your hands, and interpret what you see. Using your imagination you are transported into a fictional world. However, the majority of readers share their love for the genre with others. In this way you experience pleasure twice: once in private by reading and once in public by being a fan. Role-model: ?Reading the Romance? by Radway ? the author uses ethnography to investigate why romance novels are so popular among women and what is really happening when people read by studying a book club and the bookstore the club members frequent.

Consumption as production. Objective: investigate the performance of fandom through the creative re-appropriation of established characters. Internet culture has made more visible the tendency of fans to use beloved characters and themes as templates for their own creations and self-expressions including cosplay, fanfic, animated GIFs, remix and mash-up just to scratch the surface. Is increased visibility making this form of fandom increasingly popular? Role-model: ?Textual Poachers? by Jenkins ? author uses theory from De Certeau to talk about how sci-fi and fantasy fans engage in self-expression by embezzling bits and pieces from their favorite universes and re-presenting them in various forms.

Ethnography as pop culture. Objective: use whatever genre of pop you are interested in as the mode of communication with your readership. Anthropology in particular seems to struggle in communicating its findings to the wider public. Appropriating popular genres could be one model for reimagining ethnography is especially well suited for the study of pop culture. Role model: ?Shane, the Lone Ethnographer? by Galman ? the author uses the comic book format in place of conventional text to communicate introductory ethnographic topics to readers.

II.

There are two vulnerabilities to the academic study of popular culture that are (possibly?) unique to this particular topic. One ? few academics can hope to match the total genre mastery of superfans and thus leave themselves open to critique for ?not getting it? on a very basic level. Two ? pop culture is by definition ephemeral and dominated by fads, likewise the academic critique of pop culture does not age well; whatever hot topic you write about today will quickly fall out of fashion.

Back in Graeber?s secret lair, he?s moving into a critique of super hero movies. But first he opts to look at comic books themselves and this is where things start to get Freudian. Citing Eco, the author notes that comics share with dreams an obsession with repetition.

The plot is almost always some approximation of the following: a bad guy, maybe a crime boss, more often a powerful supervillain, embarks on a project of world conquest, destruction, theft, extortion, or revenge. The hero is alerted to the danger and figures out what?s happening. After trials and dilemmas, at the last possible minute the hero foils the villain?s plans. The world is returned to normal until the next episode when exactly the same thing happens once again.

Here we might observe that, as per my methodological discussion above, anthropology is better suited to studying people than plots. Maybe it?s my closeted structuralism, but in anthropological studies of narrative forms the plot is, sometimes, beside the point. What narratives mean to the people who use them and traffic in their symbolism is a far more interesting set of questions.

Graeber does go on to make a keen observation that I have not heard in comics circles before: whereas villains are constantly engaged in some creative project or another, the hero only ever reacts and seldom engages in such projects of their own. This really speaks to me on an intuitive level and I think it might pan out to be true if we inventoried a representative sample of universes. Just consider Ozymandias from ?The Watchman? (1987), a hero who becomes a villain once he takes on a world changing project!

While I?m sympathetic to Graeber?s leftist political project, his essay also highlights the difficulties of using theory to navigate the realms of pop culture. While the author moves to suture consuming comic books and consuming movies it?s still apples and oranges to me. Status in comic book fandom, like jazz or baseball fandom, is measured out by the accumulation of esoteric factoids and errata (perhaps demonstrating that level of mastery is part of the appeal). But even I can tell you this:

Batman on the page and Batman on the big screen are fundamentally not the same person.

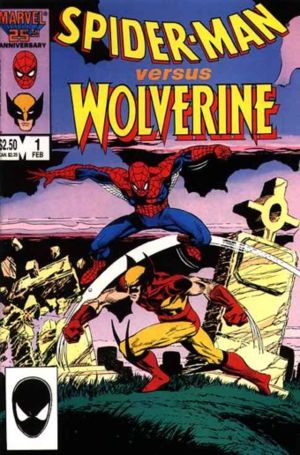

This conflation of book and movie is driven home by the art, presumably chosen by the design staff at The New Inquiry, to accompany the essay. The addition of vintage comic book covers makes the essay more appealing visually and some of them are supremely evocative of the author?s subject, as with the first one which features Lex Luther dreaming of Superman. But comic book superheroes reside in complex universes, the knowledge of which fans covet and use to authenticate their prestige. There are canons, alternate universes, spin-offs, and endless debate about which is the proper heading for any given story. Let?s not even get started on the ?What if?? series.

The result is often a self-contradictory mess. Just check out this brief synopsis of Bane, the villain from The Dark Knight Rises. When a movie director goes to translate this mess to the screen the result is like that diagram in Latour?s ?We Have Never Been Modern?: in the realm of the real there is a tangle of meaning, but modernity only ever allows us to represent it to ourselves as order. The result is we think we have created progress when in reality we have not, this is why Nolan?s was an impossible task.

So all the Freud and the lesson on how law is based on violence leads to this: the superhero needs the villain just as the cop needs the criminal. Without villains we?d have no need for heroes. Superheroes themselves aren?t fascists, Graeber writes, ?They are just ordinary, decent, super-powerful people who inhabit a world in which fascism is the only political possibility.?

This is not the ordinary way of looking at superheroes. Just as easily one could have used Freud to read the dream of comic books as wish fulfillment. The reader (likely a boy) holds an ambiguous social status: privileged because he is male, disempowered because he is not an adult. The superhero then offers a child?s fantasy of what the adult world is like. To the boy his parents are both hero and villain. Their knowledge is plainly superior to his and their power over his world seemingly limitless.

It?s also a supremely dissatisfying conclusion to a Batman fan because it gets the genre ?wrong? much as Nolan gets the character of Bane ?wrong? ? at least according to the high standards set by SMOF. And while the politics of ?Rises? and Nolan?s Batman are hot today, in a few years nobody will care about them. I mean, have you read Lawrence Grossberg?s essays on rock music? No. The kids don?t listen to rock anymore anyways.

So kudos to Graeber for attempting a critical reading of Batman in light of Occupy. But its not clobberin? time quite yet. If anthropology wants to do something with pop culture other than interpret it with critical theory, then how the hell are we going to do it? And can we do in a way that sucks less than Cultural Studies?

Matt Thompson is adjunct assistant professor in the Department of Sociology and Criminal Justice at Old Dominion University. He was once cast as a soldier in Andrew Jackson's army in a theatrical production on an Indian reservation.

Source: http://savageminds.org/2012/10/30/the-illustrated-man-vs-super-graeber/

michele bachmann tim howard west virginia rob roy gaslight justin timberlake michael dyer

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.